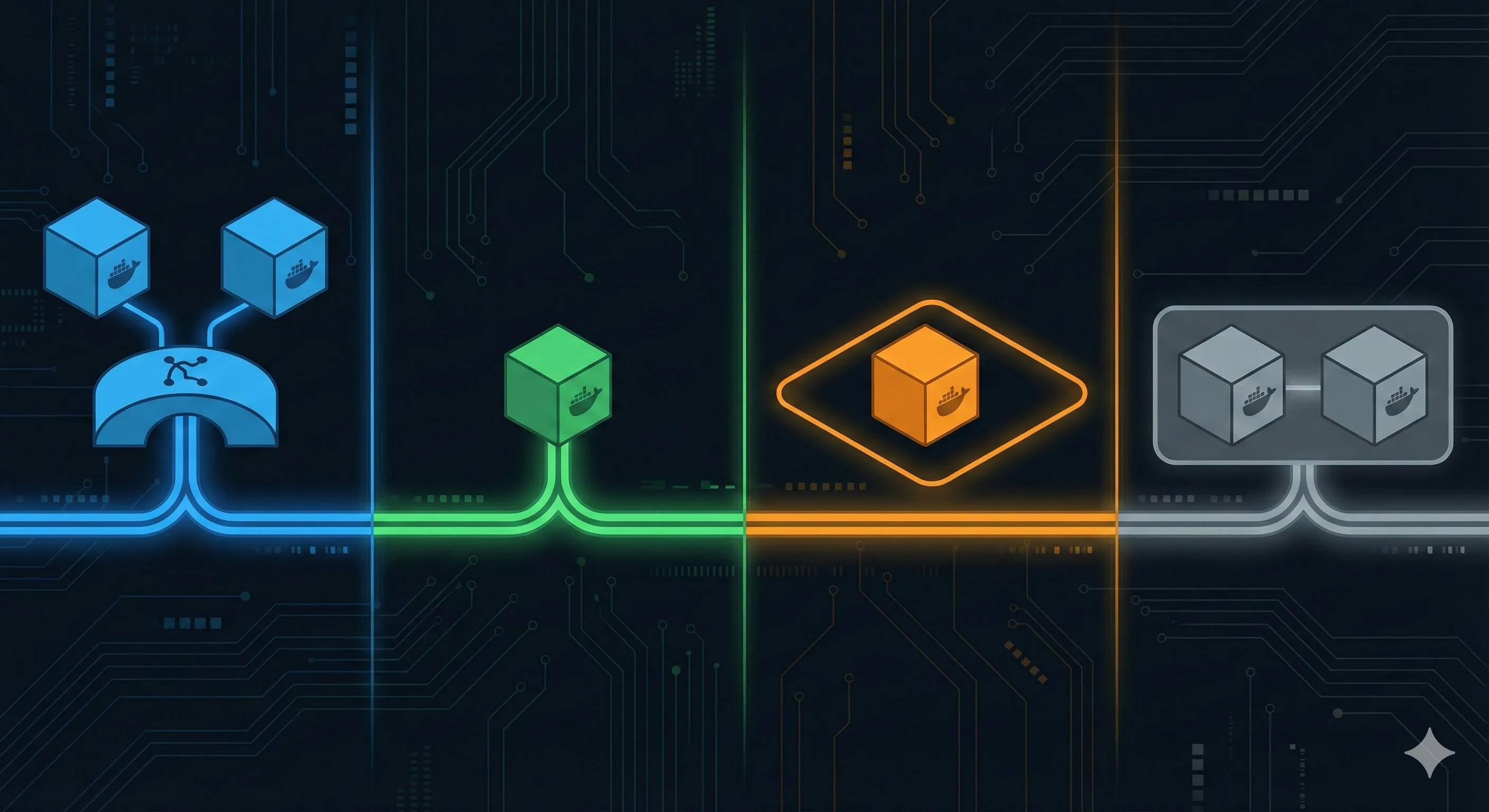

Docker Network Modes Explained: Performance Comparison and Scenario Selection of bridge/host/none/container

2 AM. I stared at that green “Container started” line in my terminal. The service was up, but curl kept timing out. Checked docker logs three times—no errors. The -p 8080:80 port mapping was configured. Network routing was fine, firewall disabled.

What was wrong?

Turns out, I had the network mode misconfigured. I thought docker run -p was all you needed, completely unaware that Docker has four network modes—bridge, host, none, and container—operating behind the scenes. Even more embarrassing: after using Docker for two years, I couldn’t explain what the docker0 bridge actually was.

If you’ve ever experienced “container runs but can’t be accessed” or feel confused about Docker networking, this article is for you. I’ll explain the differences, principles, and use cases of these four network modes in plain English. No complex Linux network namespace theory—just the practical stuff you actually need to know.

First, Understand the “Foundation” of Docker Networking—the docker0 Bridge

What is docker0? Your Container’s “Gateway”

When you install Docker, a virtual network interface called docker0 automatically appears. Think of it as your apartment complex’s gateway—all containers (residents) need to go through it to access the internet.

Open your terminal and try this command:

ip addr show docker0You’ll see output like this:

docker0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500

inet 172.17.0.1/16 brd 172.17.255.255 scope global docker0See that 172.17.0.1? That’s docker0’s IP address. Docker assigns each new container an IP from the 172.17.0.0/16 subnet, like 172.17.0.2, 172.17.0.3, and so on.

Now check Docker’s network list:

docker network lsNETWORK ID NAME DRIVER SCOPE

7f8a2b3c9d4e bridge bridge localThe default bridge network uses the docker0 bridge under the hood.

veth pair: The Container’s “Walkie-Talkie”

docker0 alone isn’t enough. How does a container in its own “private room” (technically called a network namespace) communicate with docker0?

The answer is veth pair. Think of it as a pair of walkie-talkies: one end inside the container called eth0, the other on the host called vethXXX (like veth9a7b4c), talking to each other.

Start a container and see:

docker run -d --name test-nginx nginxCheck the host’s network interfaces:

ip addr | grep vethYou’ll see a new device starting with veth. Now look inside the container:

docker exec test-nginx ip addrThe container has an eth0 interface with IP 172.17.0.2. This eth0 and the host’s vethXXX are paired. Data packets leave eth0, instantly arrive at vethXXX, pass through docker0, then exit via the host’s network card (like eth0 or ens33) to reach the internet.

The entire path looks like this:

Container (172.17.0.2)

↓ eth0

↓ (veth pair)

↓ vethXXX

↓

docker0 bridge (172.17.0.1)

↓ NAT forwarding

↓

Host network card (e.g., 192.168.1.100)

↓

InternetLooks complicated, but it’s actually fast. Ping a container IP and you’ll see latency around a few tenths of a millisecond.

To be honest, I was confused by veth pair for a while too. Then it clicked: it’s just a virtual cable, one end plugged into the container, the other into docker0. That’s it.

Bridge Mode—Docker’s “Default Choice”

Why is bridge the default?

If you don’t specify a network mode, Docker automatically uses bridge. The reason is simple: it’s the sweet spot between isolation and usability.

Bridge mode gives each container its own IP, avoiding port conflicts while allowing easy service exposure via the -p parameter. For most scenarios, this is enough.

Example with two Nginx containers:

docker run -d -p 8080:80 --name web1 nginx

docker run -d -p 8081:80 --name web2 nginxBoth containers listen on port 80, but they’re in separate network spaces, so no conflict. Access them on the host via 8080 and 8081—Docker handles NAT port forwarding behind the scenes.

Check the network config with docker inspect web1:

"Networks": {

"bridge": {

"IPAddress": "172.17.0.2",

"Gateway": "172.17.0.1"

}

}There you go: the container gets the private IP 172.17.0.2, and the gateway is docker0’s 172.17.0.1.

Default bridge vs Custom bridge: One Key Difference

Here’s a gotcha. The default bridge network (docker0) only supports IP-based communication between containers, not container name resolution.

Try this:

docker run -d --name db mysql

docker run -it --name app alpine ping dbIt won’t work. You have to use ping 172.17.0.2 with the specific IP.

But if you create a custom bridge network:

docker network create mynet

docker run -d --name db --network mynet mysql

docker run -it --name app --network mynet alpine ping dbNow it works. Custom bridge networks have built-in DNS resolution—container names work as domain names.

This is why production environments should use custom networks instead of the default docker0—service discovery is much easier without hardcoded IPs.

The Secret Behind -p: NAT Forwarding

When you use -p 8080:80, Docker adds a NAT rule to the host’s iptables:

iptables -t nat -L -n | grep 8080You’ll see output like:

DNAT tcp -- 0.0.0.0/0 0.0.0.0/0 tcp dpt:8080 to:172.17.0.2:80Translation: all traffic to the host’s port 8080 gets forwarded to the container’s 172.17.0.2:80.

That’s why accessing http://host-ip:8080 reaches the service inside the container—Docker handles address translation for you.

Bridge Mode Use Cases

Bottom line, bridge mode suits these scenarios:

- Microservices architecture: Multiple collaborating containers needing isolation and communication (use custom bridge networks)

- Development environment: Quick service testing, default bridge works fine

- Web apps needing port mapping: Like running a blog or API service

Performance-wise, bridge mode has some NAT and veth pair overhead, but honestly, for most applications this is negligible. Real performance bottlenecks are rare, so don’t worry about it upfront.

Host Mode—The “Performance First” Choice

What is Host Mode? Direct “Bare Metal”

Host mode is brutally simple: the container skips having its own network and directly uses the host’s network stack.

Start a container with --net=host:

docker run -d --net=host --name web nginxNow the container has no independent IP, no eth0 interface—it shares the host’s network interfaces. The network config inside the container matches the host’s ip addr output exactly.

More importantly: no need for -p port mapping. If the container’s service listens on port 80, external access to host-ip:80 reaches it directly.

Where’s the Performance Advantage?

Host mode bypasses the docker0 bridge and veth pair, eliminating NAT forwarding. Data packets go directly through the host’s network card, equivalent to running a process directly on the host.

Tests show host mode is about 5-10% faster than bridge mode in high-concurrency scenarios. Doesn’t sound like much, but for latency-sensitive applications (like high-frequency trading or real-time game servers), that difference matters.

I once had a case: using Nginx as a reverse proxy handling tens of thousands of requests per second. Switching to host mode reduced P99 latency from 12ms to 9ms. Just 3 milliseconds saved, but for that project, those 3 milliseconds were worth tens of thousands of dollars.

Host Mode’s Pitfalls and Trade-offs

Performance is better, but there are plenty of gotchas:

Pitfall 1: Port Conflicts

Since you’re using the host’s ports directly, starting multiple containers listening on the same port fails immediately:

docker run -d --net=host nginx # listening on 80

docker run -d --net=host nginx # also 80, error: Address already in useSame as running two Nginx instances directly on the host. Want multiple instances? Either change the listening port inside containers, or don’t use host mode.

Pitfall 2: Container Services Must Listen on 0.0.0.0

If the container’s service only listens on 127.0.0.1, external access won’t work. It must listen on 0.0.0.0 to be accessible from outside.

Once I ran a Node.js service in host mode with app.listen(3000, 'localhost') in the code. External connections failed completely. Had to change it to app.listen(3000, '0.0.0.0') to fix it.

Pitfall 3: Loss of Network Isolation

Containers can directly access all host network resources—high security risk. If you’re running untrusted third-party code in a container, using host mode is digging your own hole.

When to Use Host Mode?

Honestly, only consider host mode when you have a real performance bottleneck. In most scenarios, bridge mode’s overhead simply isn’t a problem.

Host mode suits these scenarios:

- Monitoring tools: Prometheus, Grafana, ELK stack needing direct host resource access

- High-performance proxies: Nginx, HAProxy for load balancing when chasing minimal latency

- Databases: MySQL, Redis for network-sensitive services (but mind the security)

If your application handles a few thousand requests per second, don’t bother with host mode—bridge is fine.

None and Container Modes—“Special Purpose Only”

None Mode: Complete Network Isolation Sandbox

None mode is literal: the container has no network at all.

docker run -it --net=none alpine shRun ip addr inside the container—you’ll only see a loopback interface (lo). No internet, no access from other containers.

When to Use None Mode?

To be frank, I’ve almost never used none mode in actual work. Its use cases are extremely narrow:

- Security testing: Running untrusted code with complete network isolation to prevent data leaks

- Offline data processing: Container only does local computation, needs no network communication

- Manual network configuration: Rare cases needing completely custom network setup (like using tools like pipework to manually configure veth)

If you’re not doing security research or have special network configuration needs, you basically won’t use none mode.

Container Mode: Two Containers “Sharing Network”

Container mode lets one container use another container’s network namespace. Sounds convoluted, but an example clarifies it:

# Start a container first

docker run -d --name web nginx

# Second container shares web's network

docker run -it --net=container:web alpine shNow both containers share the same network config: same IP, same port space, same network interfaces. In the second container, localhost:80 accesses nginx directly.

Container Mode’s Typical Application: Kubernetes Pods

Kubernetes Pods are actually implemented using container mode. A Pod has multiple containers sharing one “pause” container’s network.

For example, a Pod with an application container and a sidecar log collector—they communicate via localhost without exposing ports externally.

But if you’re just using Docker without Kubernetes, container mode is rarely used. Direct bridge mode + custom networks can achieve inter-container communication with more flexibility.

The Role of These Two Modes

Bottom line: none and container are more like “low-level capabilities” than everyday solutions. They provide flexibility for special scenarios, but you won’t need them 80% of the time.

Remember:

- None mode: For complete network isolation (very rare)

- Container mode: Common in Kubernetes and other orchestration tools, rarely used with Docker alone

Practical Decision-Making: Choosing the Right Network Mode

A Decision Flowchart

Facing a specific project, which network mode should you use? Here’s a simple decision flow I’ve summarized:

Need network isolation?

│

├─ No → Performance bottleneck?

│ │

│ ├─ Yes → Use Host mode (mind security risks)

│ └─ No → Use Bridge mode (more secure)

│

└─ Yes → Need containers to communicate by name?

│

├─ Yes → Custom Bridge network

└─ No → Default Bridge networkSpecial scenarios:

- Completely no network needed → None mode

- Kubernetes Pod containers → Container mode

Scenario Recommendation Quick Reference

| Scenario | Recommended Mode | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Microservices (multi-container) | Custom bridge | Supports name resolution, good isolation |

| Single web app | Default bridge | Simple enough, one command setup |

| High-performance database/cache | Host | Reduces network overhead, but assess security |

| Monitoring tools (Prometheus/ELK) | Host | Needs direct host resource access |

| Load balancer (Nginx/HAProxy) | Host | Chasing minimal latency |

| Dev/test environment | Default bridge | Quick startup, no complex config |

| K8s Pod sidecar containers | Container | Share network with main container |

| Security sandbox/offline tasks | None | Complete network isolation |

Three Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “Host mode is always best”

Wrong. Host mode sacrifices isolation and flexibility for performance gains that are often negligible in many scenarios.

I’ve seen people run all containers in host mode, ending up with port conflicts and security issues everywhere. Performance was indeed slightly better, but maintenance costs increased tenfold.

Truth: 80% of applications work fine with bridge mode. Don’t be fooled by “better performance.”

Misconception 2: “Default bridge is good enough”

Not recommended for production. Default bridge doesn’t support container name resolution. When multiple services communicate, you have to hardcode IPs or pass IPs via environment variables—very fragile.

Creating a custom bridge network is simple:

docker network create mynet

# In docker-compose.yml just specify the networkTruth: Spend 2 minutes configuring a custom network, save hours of debugging time.

Misconception 3: “Container network problems are always wrong mode choice”

Not always. Often it’s firewall, iptables config, or DNS issues.

Troubleshooting steps:

- Ping the gateway (docker0’s IP) from inside the container

- Ping the host’s external IP

- Check iptables rules for DROP

- Check Docker daemon config (/etc/docker/daemon.json)

Truth: Mode is just step one; network troubleshooting needs to be systematic.

Advanced Tips

Tip 1: Join a Container to Multiple Networks

Sometimes containers need to connect to two networks (like frontend and backend networks):

docker network create frontend

docker network create backend

docker run -d --name web --network frontend nginx

docker network connect backend webNow the web container is on both frontend and backend networks.

Tip 2: Precise IP Allocation Control

When creating custom networks, specify subnet and gateway:

docker network create \

--driver bridge \

--subnet 192.168.10.0/24 \

--gateway 192.168.10.1 \

mynet

docker run -d --network mynet --ip 192.168.10.100 nginxUseful for scenarios needing fixed IPs (like firewall whitelists).

Tip 3: Network Troubleshooting Tools

For debugging network issues inside containers, these tools are handy:

# Install network tools

docker exec -it <container> apk add curl netcat-openbsd

# Test connectivity

docker exec <container> nc -zv <host> <port>

# View routing table

docker exec <container> ip route

# Packet capture analysis (needs host privileges)

docker exec <container> tcpdump -i eth0Conclusion

After all that, here’s a quick recap of the four network modes:

- Bridge mode: Default choice, suitable for most scenarios, use custom bridge networks in production

- Host mode: Performance priority, but sacrifices isolation—only use when you have real bottlenecks

- None mode: Complete network isolation, rarely used

- Container mode: Network sharing, mainly used in Kubernetes

Remember one thing: There’s no best mode, only the most appropriate one.

If you’re new to Docker, start with default bridge. Adjust when you hit specific problems: switch to custom bridge if service discovery is a pain, consider host if performance truly isn’t enough. Don’t obsess over which mode is “optimal” from the start.

My suggestion: get hands-on. Create a custom network, start a few containers, test if they can communicate by container name. Actually running it once is worth more than reading 10 articles.

If you encounter Docker network problems in real projects, feel free to leave a comment. This is deep water, but mastering these basic concepts lets you solve 80% of problems on your own.

FAQ

What are Docker's four network modes?

• bridge (default, isolated containers via docker0)

• host (shares host network, best performance)

• none (no network access)

• container (shares another container's network namespace)

Which network mode should I use?

Use host mode only when you need maximum performance and can accept less isolation.

Use none for security-sensitive containers.

What is docker0 bridge?

It acts as a gateway for containers, assigning IPs from 172.17.0.0/16 subnet.

All bridge mode containers connect through docker0.

How do containers communicate in bridge mode?

Use `docker network create` to create custom networks for better organization and isolation.

What's the performance difference between bridge and host mode?

• No NAT overhead

• Best performance

Bridge mode:

• Adds slight overhead

• Better isolation

For most applications, the performance difference is negligible.

Can I use host mode on Mac or Windows?

On Mac/Windows, Docker runs in a VM, so host mode isn't available.

Use bridge mode with port mapping instead.

How do I troubleshoot container network issues?

• `docker network ls` to list networks

• `docker network inspect` to see details

• `docker exec container ping` to test connectivity

• `ip addr show docker0` to check bridge interface

Check port mappings and firewall rules.

11 min read · Published on: Dec 17, 2025 · Modified on: Feb 5, 2026

Related Posts

AI Keeps Writing Wrong Code? Master These 5 Prompt Techniques to Boost Efficiency by 50%

AI Keeps Writing Wrong Code? Master These 5 Prompt Techniques to Boost Efficiency by 50%

Cursor Advanced Tips: 10 Practical Methods to Double Development Efficiency (2026 Edition)

Cursor Advanced Tips: 10 Practical Methods to Double Development Efficiency (2026 Edition)

Complete Guide to Fixing Bugs with Cursor: An Efficient Workflow from Error Analysis to Solution Verification

Comments

Sign in with GitHub to leave a comment